Lead Author: Brook Baker

Co-submitters: Co-submitters: Professor Yousuf Vawda, University of KwaZulu Natal, Faculty of Law; Marcus Low, Treatment Access Campaign S.A.; Morgane Ahmare, Coalition-Plus; Saoirse Fitzpatrick, Stop AIDS and Health Poverty Action; Alienor Devaliere, Health Action International; Nuria Homedes, Salud y Farmacos USA; Andrea Carolina Reyes Rojas, Mision Salud Columbia; Maria Lorena Di Giano, Fundicion Grupo Efecto Positivo – Argentina and Red Latinoamericana por el Acceso a Medicamentos (RedLAM); Ludice Lopez Tocon, Health Action International LAC; Luz Marina Umbasia B., Fundacion IFARMA, Marcela Vieira, Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS

Organization: Health Gap; Northeastern University School of Law

Country: USA

Abstract

This contribution calls for radical reform of global and national intellectual property norms on medical technologies for all health needs. It focuses on progressive realization of the right of health and universal, equitable, and affordable access to needed health technologies. This contribution must be considered in combination with other contributions dealing more explicitly with the need to provide adequate funding and effective incentive systems for innovation, for example, the R&D Agreement contribution put forward by MSF, KEI, and others. Efforts to scale back IP rules must be complemented by alternative means to provide resources needed to develop and market products meeting essential health needs.

The current system of global norms requiring strong patent, data, and copyright protections for health technologies results in exclusive rights that ordinarily preclude competition and grant supra-competitive pricing power to right holders. Right holders seek high prices to provide resources for future research and development, marketing, infrastructure, and investor returns. These high prices are unaffordable to the vast majority of the world’s population even in rich countries. Moreover, this system fails to produce medicines for health needs where markets are not lucrative.

This contribution calls for eventually exempting all health technologies for all health conditions from IP protections in international, regional, bilateral, and national law. It calls for an explicit exemption of medical technologies from patent, copyright, and data protections in the WTO TRIPS Agreement, in trade agreements, and in national legislation. It calls for unenforceability of investor rights concerning health technologies. It is designed to encourage robust competition at efficient economies-of-scale leading to lowest, possible sustainable pricing and reduced supply interruptions. Generic producers would be required to meet global good practice in manufacturing and distribution. Nonetheless, to be implementable, policy makers must also replace IP protections with other incentives to resource health-driven innovation.

Submission

Introduction – Statement of the Problem

The global human rights regime contains an enforceable right to health, including the right of access to essential medicines and to the benefits of scientific advancement. These rights are enforceable against one’s own State, but there are also international obligations imposed on other States, multilateral institutions, and private entities to respect and protect the right to health. The current, overlapping regimes of intellectual property rights (IPRs) interfere with the progressive realization of the right to health and of access to health technologies, most commonly for poorer people, but increasingly for people everywhere, even in rich counties. The current intellectual property (IP) system fails to deliver both optimal innovation and universal access to needed medical technologies.

On the innovation side, IPRs are inefficient in several ways: (1) health R&D is driven by market returns from wealthy countries and wealthy patients, not health needs; (2) certain health condition and certain populations, including poor people, children, and marginalized populations, are neglected; (3) R&D is often focused on gaining market share and advantage rather than on patient needs; (4) R&D is conducted secretly and in silos producing duplication, waste, and tunnel vision; (5) too little research is focused on basic science and long-horizon research; (6) patenting of research tools and platforms retards downstream research; (7) patent thickets thwart incremental, follow-on, and break-through innovation; and (8) lax patent standards lead to the proliferation of R&D efforts focused on trivial, secondary patents that extend periods of exclusivity. Contrary to the claims of right holders, governments, and industry-sponsored think tanks, enhanced IP protections do not contribute to development in most low- and middle-income countries and do not promote direct foreign investment, indigenous innovation, technological growth. In fact, the vast majority of health technology patent claims are filed by large transnational firms (with the growing exception of China).

More problematically, global, regional, bilateral, and national IP regimes adversely affect universal, equitable, and affordable access to health technologies, which should be treated as a global public good. An IP-based system of exclusive rights gives medical technology right holders the power to exclude competition and to set prices at what the market will bear. When the market impacts health, and indeed life itself, the monopoly right holder has an even stronger upper hand. These right holders, driven by the goal of maximizing profits, usually set very high prices affordable only to those who are rich, who have medical insurance, or who have governments that can afford to procure the technology. Disproportionately high – indeed exclusionary – prices (compared to per capita income), even when such prices are ‘tiered’, are particularly problematic in low- and middle-income countries with high degrees of income inequality, meaning that the vast number of people who are poor go without. In economic terms, this is called dead-weight loss – in real world health terms, it can just mean death. In the current system of IP maximalization, right holders decide what price they charge, where they market, and what quantities they will produce. Pharmaceutical right holders also have strong incentives to engage in what is euphemistically called product “life-cycle” management, namely efforts to evergreen existing patent exclusivity with secondary patents on minor modification of the chemical/biologic entity, the formulation, and/or dosage; new uses, and new processes. Finally, the monopoly rents available on medical technologies encourages right holders to seek longer and stronger forms of IP protection nationally, regionally, and internationally through trade agreements and otherwise – the IP ratchet always spirals upward.

Proposed IPR reform concerning medical technologies

This contribution explicitly supports and is supplemental to the R&D Agreement contribution submitted by MSF, KEI, and others that focuses on rationalizing and strengthening incentives, and legal frameworks for R&D, that promote innovation and access to health technologies. However, this contribution focuses primarily on access and calls for the dismantling of global, regional, bilateral, and national IP regimes that negatively impact the global community’s access needs. It focuses on patents, the most obvious and important source of exclusivity for right holders, but also on data and regulatory market exclusivities and linkages, trade secret law, and trademark and copyright protections, which are increasingly embedded in operating systems of diagnostics and other health technologies.

At present, the vast majority of countries are members of the World Trade Organization. As members, they are subject to the minimum standards of IP protections set forth in the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Although there are transition periods that still apply to least developed country members, most WTO members are now subject to the whole panoply of IPRs and IP enforcement mechanisms set forth in TRIPS. As such, for IP barriers to be dismantled on health technologies, it will be necessary to amend or otherwise supersede TRIPS’s application to those technologies. The proposed non-application of TRIPS to medical technologies could be accomplished as follows:

Article 6bis:

Exhaustion and Non-Application to Medical Technologies

1. For the purposes of dispute settlement under this Agreement, subject to the provisions in

Articles 3 and 4 nothing in this Agreement shall be used to address the issue of exhaustion of intellectual property rights.

2. Nothing in this Agreement shall apply to medical technologies as defined.

Definition of medical technologies: pharmaceutical and biologic products, vaccines, diagnostics, and related health technologies.

Article 7bis

Right to health and other objectives

The protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare and to the fulfillment of the human right to health, and to a balance of rights and obligations. Members shall not implement the Agreement in a manner that weakens the promotion or protection of the right to health and of access to health technologies.

Article 13 bis

Exemptions, limitations and exceptions

Members shall confine limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the interests of the right holder. This section shall not apply to copyrights, trademarks and related rights embedded in health technologies, including the systems of internet or other transmission of health-related information from a health technology elsewhere.

Article 27(1) bis

Subject to the provisions of paragraph 2, 3, 6, and 7, patents shall be available, whether for products or processes, in all fields of technology, except health technologies, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are industrially applicable.

Article 27(4) bis

Members shall exclude health technologies.

Article 39.3bis

3. Members, when requiring, as a condition of approving the marketing of pharmaceutical or of agricultural chemical products which utilize new chemical entities, the submission of undisclosed test or other data, the origination of which involves considerable effort, shall protect such data against unfair commercial use. In addition, Members shall need not protect such data against disclosure, except where such disclosure is necessary to protect the public in the public interest, or unless steps are taken to ensure that the data are protected from unfair commercial use.

In addition to amending the TRIPS Agreement, it will be necessary to formally amend multiple regional and bilateral trade and economic partnership agreements and investment treaties/provisions. Many regional and bilateral trade agreements contain IPR provisions similar to those in the TRIPS Agreement and/or provisions that are TRIPS-plus. These agreements are binding on parties, so to achieve the desired IPR reform, such agreements need to be amended to remove IPR protections on health technologies. There are far too many such agreements to list or discuss, but reform must be undertaken. Similarly, it will be necessary to reform the WIPO Patent Cooperation Treaty to exempt health technologies from patent filings and to do the same with respect to the Harare Protocol (relating to the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization), the Bangui Agreement (relating to the African Intellectual Property Organization), the Eurasian Patent Convention (affecting the Eurasian Patent Organization), and any other relevant regional patent processing entities.

Addressing agreements on IPRs is not enough unless investment agreements are also amended to remove investor protections on health technologies. Just as there was a carve-out for Tobacco in the recently negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (however imperfect), there could be a new and stronger carve out for health technologies. At present, more and more investment agreements directly cover IPRs and give foreign investor rights to bring private investor-state-dispute-settlement (ISDS) claims directly to private arbiters. These new IPR enforcement rights are particularly dangerous as they give right holders powers to directly challenge government IP policy and decisions that adversely impact their expectation of unbridled profits, as is currently claimed in the US$500 million Eli Lilly v. Canada ISDS case.

To complete the reform process, it will be necessary to revise IP laws at the national level to incorporate the health technology exclusion. This will be an enormous undertaking technically and politically, even more so where IP is constitutionally protected. Even in these circumstances, if the interests of inventors and creators are adequately protected under a new R&D incentive system, then constitutional requirements may well be satisfied. Similarly, protecting the interests of creators and sometimes inventors under international human rights regimes does not require resort to IPRs. The economic and attributional interests of inventors and creators can be met through other means.

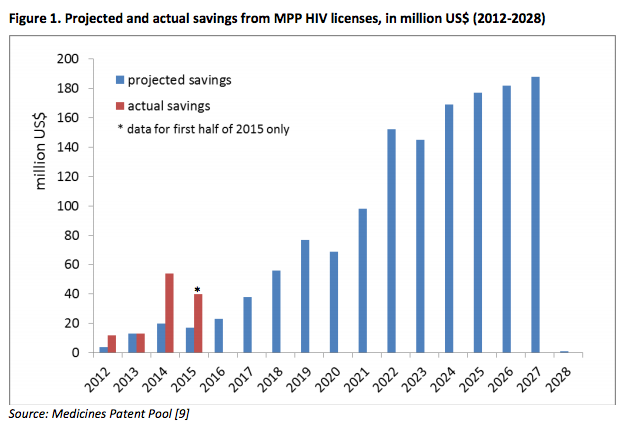

The medical innovation system needs robust funding and effective incentive systems to reward researchers and product developers. However, the removal of IP barriers is designed to create a global market for health technologies, not the fragmented markets that result from more modest IP reform efforts, e.g., opposition systems, compulsory licenses, and voluntary licenses. Moreover, a health technology terrain without IPRs encourages follow-on research, product optimization, and technology adaptation. Countries could phase out IP protections at the same time they scale up other measures – voluntary or mandatory that are coordinated globally – that seeks to reward innovation through other incentives. An aggregated global market would promote competitive markets for producers who could manufacture at efficient economies-of-scale and simultaneously guarantee more redundant and secure sources of supply. Public policy measures might be needed to ensure a healthy and sustainable market, including prices controls where competition is weak, emerging, or dying, and to prevent price collusion and other anticompetitive behaviors. Procurement systems should be coordinated and calibrated to help guarantee the maintenance of sustainable and competitive markets, while allowing for the eventual obsolescence of particular health technologies.

In addition, countries need to impose rigorous product registration standards and procedures and post-market surveillance to guarantee the safety, quality, and efficacy of health technologies. Although regional harmonization of regulatory standards and procedures might certainly be desirable, all countries should seek to ensure that health technologies are produced and distributed pursuant to globally accepted good practice standards.

A potential side benefit of the removal of IP protections on health technologies is the accelerated development of health technology capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Although the goal of total national or even regional health-technology capacity might be elusive, domestic manufacturers will have substantially more freedom to operate in an IPR-free zone. These opportunities would certainly strengthen technological capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Countries could focus their R&D efforts on domestic needs and on optimization, adaptation, and repurposing of existing health technologies to local realities.

Impact on Policy Coherence

The current IP system creates pervasive global incoherence between the right to health and the monopoly interests of IP right holders, except to the extent that the patent system and related data protections and medical technology copyrights incentivize some R&D that focuses on market returns. Global health interests with respect to all medical conditions would be advanced if IP barriers did not preclude better-targeted R&D and greatly expanded access to much more affordable health technologies. The resulting savings could not only be poured back into R&D incentive mechanisms that better target and reward innovation that responds to essential health needs, they would also allow government and individual investments in other priority areas, including health promotion and spending on other public, merit, and private goods.

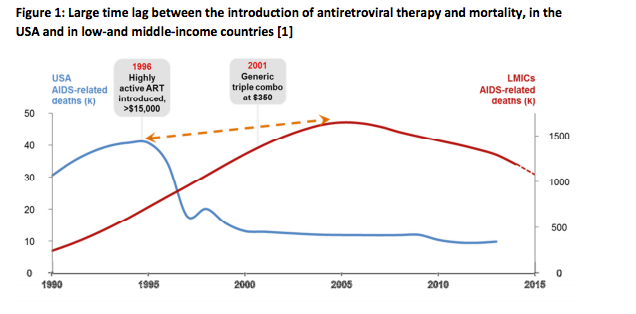

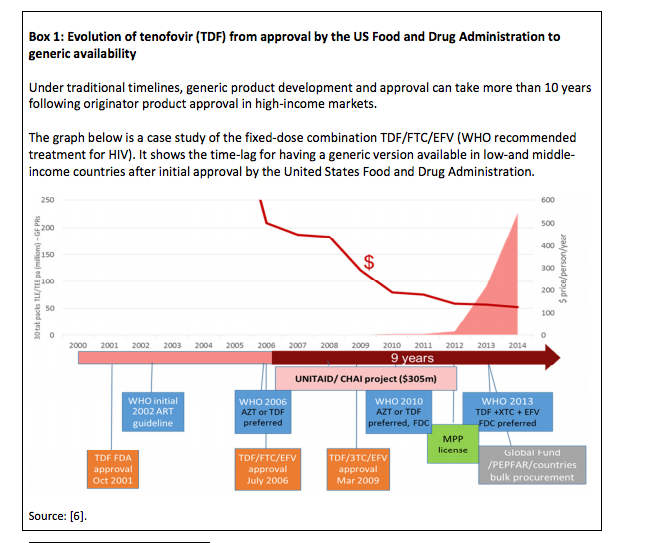

Impacts on Public Health

The impacts on public health will be enormous. If replaced by a robust R&D incentive system that does not rely upon market monopolies, the elimination of IPR barriers would not only provoke more therapeutically targeted research benefitting all people with respect to all health conditions, it would lead to a revolution in access to health-promoting and health-sustaining technologies. For the first time, if health technologies were as affordable as possible, it would be possible to prevent and treat human illness and disease universally and equitably. No longer would access be dependent solely on place of birth, national income, or personal wealth. Health spending on health technologies would in all probability decrease substantially allowing even more cross-subsidization of health promotion, prevention, treatment, and cure both internationally and domestically. Allocating funding to needs driven R&D, whether to basic research, push funding or pull incentives, would reward true innovation. Instead of rationing health technologies, as currently being done for hepatitis C, countries would for the first time be able to consider true universal access. Universal access is particularly important in overcoming the scourge of infectious diseases, where treatment for all provides herd immunity for diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis, and now Zika. No longer would neglected diseases like Ebola be neglected. Research could be targeted not only on neglected diseases but neglected populations such as pregnant women and children, and the resulting health technologies could be more widely and equitably available. Similarly, the painful global disregard of chronic non-infectious diseases in low- and middle-income countries could be addressed. Instead of newer cancer, arthritis, and orphan disease medicines, e.g., Kadcyla and Solaris, being priced at astronomical levels – unaffordable even in rich countries, these newer medicines could be offered more widely and more affordably.

Impact on Human Rights

Since the right to health and the right of access to well-adapted, affordable health technologies of assured quality are fundamental, the elimination of IPRs on health technologies will greatly enhance the ability of duty bearers to fulfill their human rights obligations. Cash strapped payers across the globe, even rich ones, are struggling to keep pace with price escalation of health technologies. Poorer countries simply cannot do so without price concessions and even then only with donor assistance in purchasing health technologies. But increasingly middle-income countries, where 70-plus percent of the global poor live, cannot afford IP-based prices on essential health technologies. Excessive pricing leads to rejecting needed technologies, rationing, and/or diverting funds from other critical areas of public and private investment. Under conditions of scarcity, exacerbated by high prices, equity is often sacrificed. Not only are the poor and harder to reach rural populations often left behind, but also politically unpopular persons and groups are often excluded from health services. Regrettably, in many contexts, women and children are left behind as their health needs are neglected.

The elimination of IPRs on health technologies would greatly impact the actions of other States and private corporations that at this point are too often focused on increasing IP protections and extracting excess profits. The temptation to negatively impact the right to health and the legal tools to do so are dismantled under this IP reform proposal. In this new era, private companies succeed and are rewarded for R&D that serves the public interest, research that has added diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventative value. Countries would no longer be subject to the relentless lobbying of IP-based health technology companies and can instead work more proactively towards to the global public good of best attainable health for all.

Implementation

Politically, this is likely to be the most challenging and difficult contribution received by the High Level Panel. In a nutshell, it will disrupt the business model of a very rich and powerful set of industries that survive and thrive on a steady and increasing rich diet of expansive IP protections. Moreover, many of these industries have succeeded in capturing the political leadership of their home countries to advance their IP hegemony both domestically and abroad. However, there is a new recognition and a growing clamor that pharmaceutical prices are escalating out of control, as are medical costs more generally. There is increased inequality within and between countries, with clear impacts even in wealthy countries. Even political elites are beginning to hear the public outcry and are responding to the excesses of monopoly pricing. The innovation reforms previously proposed, including for an R&D treaty, cannot succeed unless IP protections for health technologies are simultaneously dismantled. Parenthetically, it may well be that this contribution would have greater chances of success if it were broadened to cover other global public goods including green/climate-control technologies, educational and scientific resources, agricultural and food resources and technologies, and digital technologies.

This contribution and its proposal for major IP reform – indeed IP dismantling – needs to be raised within the UN system. It may be that there are more gradual reform possibilities along the way, for example, a moratorium on the enforcement of the TRIPS Agreement with respect to health technologies, preliminary exclusion of IP protections for essential medicines, compensation and liability schemes in place of exclusive rights, stronger research exceptions and compulsory licensing opportunities, etc. What is clear is that the current push for TRIPS-plus IP protections is unsustainable. As a starting point, there should clearly be a moratorium on TRIPS-plus demands in trade agreements. Similarly, it is clear that all countries, rich and poor, should amend their IP regimes to take advantage of all TRIPS-permissible flexibilities. Nonetheless, these incremental reforms do not go far enough to overcome policy incoherence that undermines innovation, the right to health, and public health more broadly. The time for incrementally and eventually dismantling an ineffective, inequitable, and dangerously expensive IP regime on health technologies has come.

Bibliography and References

Critiques of IP regime

Critiques by Major International Initiatives

COMMISSION ON MACROECONOMICS AND HEALTH, MACROECONOMICS AND HEALTH: INVESTING FOR HEALTH IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (2001) (finding inadequate market incentives for R&D on developing country diseases, favoring more use of compulsory licenses, and the establishment of a global Health Research Fund), http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42435/1/924154550X.pdf

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS, INNOVATIONS AND PUBLIC HEALTH (2006) (finding inadequate market incentives for diseases affecting developing countries, the need for new R&D financing mechanisms, and the need for increased adoption and use of TRIPS flexibilities and avoidance of TRIPS-plus measures), http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/documents/thereport/ENPublicHealthReport.pdf?ua=1

WHO, GLOBAL STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON PUBLIC HEALTH, INNOVATION AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (2011) (finding inadequate market incentives for R&D on type II and III diseases and encouraging and supporting the application and management of intellectual property in a manner that maximizes health-related innovation, especially to meet the research and development needs of developing countries, protects public health and promotes access to medicines for all, as well as explore and implement, where appropriate, possible incentive schemes for research and development), http://www.who.int/phi/publications/Global_Strategy_Plan_Action.pdf

The 45 Adopted Recommendations under the WIPO Development Agenda (2007) (making multiple recommendations on adapting IP policies to the needs and interests of developing countries), http://www.wipo.int/ip-development/en/agenda/recommendations.html

Critiques of patents as incentives for innovation

Adam Mannan & Alan Story, Abolishing the product patent: a step forward for global access to drugs, in POWER OF PILLS: SOCIAL, ETHICAL AND LEGAL ISSUES IN DRUG DEVELOPMENT, MARKETING AND PRICING, 183 (J. Cohen, P. Illingworth and U. Schüklenk Eds., Ann Arbor, Mi: Pluto Press 2006) (also advocating for abolishment of product patents on medicines).

Michele Boldrin & David K. Levine, Does Intellectual Monopoly Help Innovation?, 5 REV. OF LAW & ECON. 991-1024 (2009) http://www.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1438&context=rle

Michele Boldrin & David K. Levine, The Case against Patents, Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis Working Paper Series 2012-035A (2012) http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2012/2012-035.pdf

Boldrine & Levine: AGAINST INTELLECTUAL MONOPOLY, CH. 9: THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY (2007) http://levine.sscnet.ucla.edu/papers/anew09.pdf

Critiques of IP’s impact on access to medicine

Claudia Chams, Ben Prickril & Joshua Sarnoff, Intellectual property and medicine: Toward global health equity, in INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: RECENT TRENDS AND FUTURE SCENARIOS (Public Int’l I.P. Advisors 2011) http://piipa.org/images/IP_Book/Chapter_2_-_IP_and_Human_Development.pdf

NEGOTIATING HEALTH: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ACCESS TO MEDICINES (Pedro Roffe, Geoff Tansey & David Vivas-Eugui eds., 2006)

Project on IPRs and Sustainable Development, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT (2003) http://www.ictsd.org/pubs/ictsd_series/iprs/pp/pp_1intro.pdf

Ellen ‘t Hoen, THE GLOBAL POLITICS OF PHARMACEUTICAL MONOPOLY POWER (2009) http://www.msfaccess.org/fileadmin/user_upload/medinnov_accesspatents/01-05_BOOK_tHoen_PoliticsofPharmaPower_defnet.pdf

THE TREATMENT TIMEBOMB: REPORT OF THE INQUIRY OF THE ALL PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON AIDS INTO LONG-TERM ACCESS TO HIV MEDICINES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD (2009) http://www.aidsportal.org/repos/APPGTimebomb091.pdf

Sean Flynn, Aidan Hollis, & Mike Palmedo, An Economic Justifications for Open Access to Essential Medicine Patents in Developing Countries, J. LAW, MEDICINE & ETHICS 184-2008 (2009) www.wcl.american.edu/pijip/go/fhp2009

Critiques of IP’s effectiveness in promoting development and innovation in developing countries

Brook K. Baker, Debunking IP-for-Development: Africa Needs IP Space Not IP Shackles in INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC LAW AND AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT, 82-110 (Laurence Boulle, Emmanuel Laryea & Franziska Sucker eds. 2014) (and sources cited)

Less Brantetter, Raymond Fisman, C. Fritz Foley & Kamal Saggi, Intellectual Property Rights, Imitation, and Foreign Direct Investment: Theory and Evidence, NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES 13033 (April 2007) http://www.nber.org/papers/w13033.pdf?new_window=1

Yi Qian, Do National Patent Laws Stimulate Domestic Innovation in a Global Patenting Environment?: A Cross-Country Analysis of Pharmaceutical Patent Protection, 1978-2002, 89 REV. ECON. & STAT. 436-453 (2007) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1024829#PaperDownload

Tzen Wong, Intellectual property through the lens of human development in INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: RECENT TRENDS AND FUTURE SCENARIOS (Public Int’l I.P. Advisors 2011) http://www.piipa.org/images/IP_Book/Chapter_1_-_IP_and_Human_Development.pdf

Petra Moser, Patents and Innovation: Evidence from Economic History, 27:1 J. ECON. PERSPECTIVES 23-44 (2013), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/jep.27.1.23

Critiques of abuses of IP by right holders

European Commission Competition DG, PHARMACEUTICAL SECTOR INQUIRY: PRELIMINARY REPORT – EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (2008) http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/pharmaceuticals/inquiry/exec_summary_en.pdf

Susan K. Sell, THE GLOBAL IP UPWARD RATCHET, ANTI-COUNTERFEITING AND PIRACY ENFORCEMENT EFFORTS: THE STATE OF PLAY (June 9, 2008) http://www.iqsensato.org/wp-content/uploads/Sell_IP_Enforcement_State_of_Play-OPs_1_June_2008.pdf

Critiques of secondary patent evergreening strategies

Carlos M. Correa, TACKLING THE PROLIFERATION OF PATENTS: HOW TO AVOID UNDUE LIMITATIONS TO COMPETITION AND THE PUBLIC DOMAIN, South Centre Research Paper (2014), http://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-52-august-2014/

Carlos M. Correa, Pharmaceutical Innovation, Incremental Patenting and Compulsory Licensing, SOUTH CENTRE RESEARCH PAPER 41 (2011) http://www.southcentre.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1601%3Apharmaceutical-innovation-incremental-patenting-and-compulsory-licensing&catid=41%3Ainnovation-technology-and-patent-policy&lang=en

Natalie Vernaz et al., Patented Drug Extension Strategies on Healthcare Spending: A Cost-Evaluation Analysis, 10:6 PLOS MEDICINE e1001460 (2013)

Andrew Hitchings, Emma Baker & Teck Khong, Making medicines evergreen, 345 BMJ e7941 (2012)

Tahir Amin & Aaron S. Kesselheim, Secondary Patenting Of Branded Pharmaceuticals: A Case Study Of How Patents On Two HIV Drugs Could Be Extended For Decades, 31 HEALTH AFFAIRS 2286-94 (2012) http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/31/10/2286.full.html

Amy Kapczynski, Chan Park & Bhaven Sampat, Polymorphs and Prodrugs and Salts (Oh My!): An Empirical Analysis of “Secondary” Pharmaceutical Patents, 7:12 PLOS ONE e49470 (2012), http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchObject.action?uri=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0049470&representation=PDF

Reed F. Beall, Jason W. Nickerson, Warren A. Kaplan & Amir Attaran, Is Patent “Evergreening” Restricting Access to Medicine/Device Combination Products?, PLOS ONE 121(2): e0148939, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0148939

Critiques of IP-based R&D priorities and efficiency

Donald Light & Joel Lexchin, Pharmaceutical research and development: what do we get for all that money?, 344 BMJ e4348 (2012) http://www.bmj.com/highwire/filestream/597113/field_highwire_article_pdf/0/bmj.e4348

Donald Light & Rebecca Warburton, Demythologizing the high cost of pharmaceutical research, 6 BIOSOCIETIES 34-50 (2011) http://www.pharmamyths.net/files/Biosocieties_2011_Myths_of_High_Drug_Research_Costs.pdf

Jack Scannel et al., Diagnosing the declines in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency, 11 NATURE REVIEWS 191-200 (2012) http://www.nature.com/nrd/journal/v11/n3/pdf/nrd3681.pdf

Michael Hay et al., Clinical Development success rate for investigational drugs, 32:1 NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY 40-51 (2014), http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v32/n1/pdf/nbt.2786.pdf

PLoS Medicine, Disease Mongering Collection (2006) http://www.ploscollections.org/article/browseIssue.action?issue=info:doi/10.1371/issue.pcol.v07.i02

Critique of IP’s Impacts on follow-on research

Medical Research and Human Experimental Law, REPORT OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HEALTH (NIH) WORKING GROUP ON RESEARCH TOOLS (presented to the Advisory Committee to the Director, June 4, 1998) (finding that many researchers were frustrated by growing difficulties and delays in negotiating licensed access to research tools and that access was often costly, burdensome to negotiate, and sometimes unattainable) http://biotech.law.lsu.edu/research/fed/NIH/researchtools/Report98.htm#compet

Michael S. Mireles, An examination of patents, licensing, research tools, and the tragedy of the anticommons in biomedical innovation, 38 University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 141, 191–194 (2005).

John P. Walsh, Ashish Arora & Wesley M. Cohen, The patenting of research tools and biomedical innovations, in PATENTS IN THE KNOWLEDGE-BASED ECONOMY (Wesley M. Cohen & Stephen A. Merrill eds., National Academic Press October 2003) (finding negative impacts on the use of patented genetic diagnostic), http://www.nap.edu/read/10770/chapter/11

Critiques of Impacts of Free Trade Agreements

Xavier Seuba, FREE TRADE OF PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS: THE LIMITS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENFORCEMENT AT THE BORDER, Programme on IPRs and Sustainable Development Series • Issue Paper 27 (2010) http://ictsd.org/i/publications/74589/

UNDP/UNAIDS ISSUE BRIEF, THE POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS ON PUBLIC HEALTH (2012) http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/JC2349_Issue_Brief_Free-Trade-Agreements_en.pdf

UNITAID, TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR ACCESS TO MEDICINES AND PUBLIC HEALTH (2014), http://www.unitaid.eu/en/rss-unitaid/1339-the-trans-pacific-partnership-agreement-implications-for-access-to-medicines-and-public-health

Brook K. Baker & Katrina Geddes, Corporate Power Unbound: Investor-State Arbitration of IP Monopolies on Medicines – Eli Lilly v. Canada and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (forthcoming J. INTEL. PROP. L. 2016)

Brook K. Baker, Ending drug registration apartheid – taming data exclusivity and patent/registration linkage, 34 AM. J. LAW & MED. 303-344 (2008)

Brook K. Baker, Arthritic Flexibilities for Accessing Medicines, Analysis of WTO Action Regarding Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, 14 IND. INT’L & COMP. L. REV. 613-715 (2004).

Critiques aimed at increasing use of flexibilities

UNDP, GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE: IMPROVING ACCESS TO TREATMENT BY UTILIZING PUBLIC HEALTH FLEXIBILITIES IN THE WTO TRIPS AGREEMENT (UNDP: New York, 2010)

UNDP, USING COMPETITION LAW TO PROMOTE ACCESS TO HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES A GUIDEBOOK FOR LOW-AND-MIDDLE INCOME COUNTRIES (UNDP: New York, 2014)

F.M. Abbott & R. Van Puymbroeck, COMPULSORY LICENSING FOR PUBLIC HEALTH: A GUIDE AND MODEL DOCUMENTS FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DOHA DECLARATION PARAGRAPH 6 DECISION (Washington: World Bank, 2005)

PROCESSES AND ISSUES FOR IMPROVING ACCESS TO MEDICINES: WILLINGNESS AND ABILITY TO UTILIZE TRIPS FLEXIBILITIES IN NON-PRODUCING COUNTRIES, U.K. Dept. for Int’l Development, Health Systems Resource Centre (Commissioned Sept. 2004) http://www.iprsonline.org/resources/docs/Baker_TRIPS_Flex.pdf

WHO, GLOBALIZATION, TRIPS AND ACCESS TO PHARMACEUTICALS, WHO POLICY PERSPECTIVES ON MEDICINES NO. 3 (Geneva: WHO, 2001), WHO/EDM/2001.2, whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_EDM_2001.2.pdf

Critiques based on Human Rights and right of access to medicines for all

Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, INTEGRATING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS AND DEVELOPMENT POLICY (London: The Commission, 2002) (finding that the demands of healthcare should determine IPRs and that IPRs should be monitored to ensure they meet healthcare objective and do not interfere with developing country access and urging developing countries to adopt maximum patenting standards and flexibilities in domestic legislation), http://www.iprcommission.org/papers/pdfs/final_report/ciprfullfinal.pdf

GLOBAL COMMISSION ON HIV AND THE LAW: RISKS, RIGHTS & HEALTH (2012) (finding that TRIPS flexibilities have proved insufficient in obviating the shortages of affordable medicines that TRIPS itself has contributed to creating and that the TRIPS regime was not delivering promised innovation, and calling for a moratorium on the enforcement of pharmaceutical IP, http://www.hivlawcommission.org/resources/report/FinalReport-Risks,Rights &Health-EN.pdfOHCHR, The Impact of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights on Human Rights: Report of the High Commissioner, UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/13 (27 June 2001), paras. 42-44

UNAIDS & OHCHR, INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES ON HIV/AIDS AND HUMAN RIGHTS, 2006 CONSOLIDATED VERSION, GUIDELINE 6 (revised) (ensuring that international agreements, such as those dealing with intellectual property, do not impede access to health care technologies; ensuring that their domestic legislation incorporates to the fullest extent any safeguards and flexibilities in such international agreements that may be used to promote and ensure access to medicines, diagnostics and related technologies, and that they make use of these safeguards to the extent necessary to satisfy their domestic and international obligations in relation to human rights; and reviewing said international agreements to ensure their consistency with human rights obligations, and amending them as necessary), http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/jc1252-internguidelines_en.pdf

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, UN Doc. A/69/299, (2014) (calling for a review of investment treaties and investor-state dispute settlement), http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N14/501/83/PDF/N1450183.pdf?OpenElement

Report of the Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, UN Doc. A/70/285 (2015) (same), http://www.rightingfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/his-report-to-the-General-Assembly.pdf.

Report of the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, UN Doc. A/70/279 (2015) (noting that patent policies and practice may divert research priorities away from matters of greatest public concern, that IP can be ineffective in stimulating necessary R&D, that there are alternative mechanisms for stimulating research, and that patents can get in the way of producing an improved dependent technology; finding that implementing unreasonably strong patent protection may constitute a violation of human rights and reaffirming that there is no human right to patent protection in article 15 of ICESCR; and calling for exploration and adoption of alternative incentive model for technological innovation), http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/243/83/PDF/N1524383.pdf?OpenElement

Brook K. Baker, Placing Access to Essential Medicines on the Human Rights Agenda, in THE POWER OF PILLS: SOCIAL, ETHICAL & LEGAL ISSUES IN DRUG DEVELOPMENT, MARKETING & PRICING 239-46 (Jillian C. Cohen, Patricia Illingworth & Udo Schuklenk eds., 2006

Yousuf Vawda & Brook Baker, Achieving Social Justice in the Intellectual Property Debate: Realising the Goal of Access to Medicines, 13 AFRICA HUMAN RIGHTS L. J. 57-84 (2013) http://www.ahrlj.up.ac.za/images/ahrlj/2013/ahrlj_vol13_no1_2013_vawda_baker.pdf

Richard Elliott, TRIPS AND RIGHTS: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW, ACCESS TO MEDICINES AND THE INTERPRETATION OF THE WTO AGREEMENT ON TRADE-RELATED ASPECTS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (2001)

Lisa Forman & Jillian Clare Kohler, Introduction: Access to Medicines as a Human Right – What Does it Mean for Pharmaceutical Company Responsibilities in ACCESS TO MEDICINES AS A HUMAN RIGHT – WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY RESPONSIBILITY (2012), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2159263

Alicia Ely Yamin, Not Just a Tragedy: Access to Medications as a Right under International Law, 21 B.U. INT’L L.J. 325 (2003), http://www.cptech.org/ip/health/cl/yamin03012004.pdf

Fred Abbott, Intellectual Property and Public Health: Meeting the Challenge of Sustainability, GLOBAL HEALTH PROGRAMME WORKING PAPER NO. 7 (2011), http://www.law.fsu.edu/events/documents/Abbott.pdf

Brook K. Baker & Tenu Avafia, THE EVOLUTION OF IPRS FROM HUMBLE BEGINNINGS TO THE MODERN DAY TRIPS-PLUS ERA: IMPLICATIONS FOR TREATMENT ACCESS, UNDP/UNAIDS Global Commission on HIV and the Law (commissioned June 2011) http://www.hivlawcommission.org/index.php/working-papers?start=10

Tenu Avafia & Brook K. Baker, Laws and Practices That Facilitate or Impede HIV-Related Treatment Access, GLOBAL COMM. ON HIV AND THE LAW WORKING PAPER (2010), http://www.hivlawcommission.org/resources/background-papers/Background-Paper-Laws-and-Practices-that-Facilitate-or-Impede-HIV-Related-Treatment-Access-2010.pdf