Submission: UNITAID

Prepared by: Karin Timmermans

Country: Switzerland

Abstract

The key points of this submission are:

- voluntary measures (notably pooled voluntary licensing) and the use of TRIPS flexibilities can be complementary, and both are important to improve access to existing medicines;

- R&D approaches that encompass the principle of “delinkage” merit to be seriously explored.

UNITAID's strength is in its positioning and ability to articulate among partners. The Medicines Patent Pool and other projects addressing intellectual property rights demonstrate UNITAID's ability to play this articulating role, as supported by evidence presented in this paper.

Submission

UNITAID SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS SECRETARY-GENERAL’S HIGH-LEVEL PANEL ON ACCESS TO MEDICINES

OVERCOMING PATENT BARRIERS: OPTIONS AND IMPACT

About UNITAID

UNITAID is engaged in finding new ways to prevent, treat and diagnose HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria more quickly, more cheaply and more effectively. It takes game-changing ideas and helps to turn them into practical solutions that can help accelerate the end of the three diseases. Established in 2006 by Brazil, Chile, France, Norway and the United Kingdom to provide an innovative approach to global health, UNITAID plays an important part in the global effort to defeat HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, by facilitating and speeding up the availability of improved health products. See also UNITAID’s other contribution entitled “Accelerating innovation: lessons learned by UNITAID”.

In line with its mandate, UNITAID supports several projects that deal with intellectual property rights. UNITAID also supports transparency in patent information, both through its projects and through the work of the Secretariat1. To date, UNITAID’s work has focused on HIV, TB and malaria. Currently, UNITAID is developing its next five-year strategy (2017-2021); alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals is one of the guiding principles in this process.

UNITAID's strength is in its positioning and ability to articulate among partners. The Medicines Patent Pool and other projects addressing intellectual property rights demonstrate UNITAID's ability to play this articulating role, as supported by evidence presented in this paper.

Key points

In response to the High Level Panel’s call for contributions that address the policy incoherence in relation to the rights of inventors, international human rights law, trade rules, and public health objectives including increased access to medicines and other health technologies, UNITAID has submitted a paper “Accelerating innovation: lessons learned by UNITAID”. UNITAID would furthermore like to submit the following.

The key points of this submission are:

• voluntary measures (notably pooled voluntary licensing) and the use of TRIPS flexibilities can be complementary, and both are important to improve access to existing medicines;

• R&D approaches that encompass the principle of “delinkage” merit to be seriously explored.

Though this submission focusses on the actual and projected impact of approaches to overcome patent barriers, institutional dynamics also matter. In particular, in UNITAID’s experience, it is important to consult stakeholders; this provides an opportunity to learn about concerns and to engage in dialogue on ways to address them.

Intellectual property rights, innovation and access

The Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health (CIPIH) has already noted that “intellectual property rights have an important role to play in stimulating innovation in health-care products in countries where financial and technological capacities exist, and in relation to products for which profitable markets exist. In developing countries, the fact that a patent can be obtained may contribute nothing or little to innovation if the market is too small or scientific and technological capability inadequate” [1].

In line with the analysis of the CIPIH, UNITAID has found that the intellectual property system provides effective incentives for innovation in some of the diseases that UNITAID focuses on – notably hepatitis C2 and HIV. For these diseases, a number of medicines have been developed and brought to market, and more molecules are in the pipeline [2,3].

As has been noted by others, this same incentive system has not worked equally well for tuberculosis [4]. Similarly, the fact that the patent system fails to effectively induce innovation for neglected tropical diseases – sometimes referred to as “type III diseases” – has been extensively discussed and explored elsewhere [1,4-6]. While UNITAID shares the global health community’s concerns about the lack of innovation for neglected tropical diseases, it is not the focus of our work or of this submission.

Access challenges

While innovation is a prerequisite for access, it is not – on its own – sufficient; in some areas where new medicines have been developed, such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C, challenges remain:

• Lack of affordability. Patents prevent generic competition. In the absence of competition, prices may be so high that people or health care systems cannot afford them. Examples include the high price of HIV medicines in the late 1990s (in 2000, the cost of HIV treatment per person per year was around US$ 10,000; unaffordable for most people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries) and the current high prices of hepatitis C medicines – which prove challenging even for many high-income countries.

• Lack of incentives to develop adapted formulations. Patent holders may lack incentives to develop certain formulations for which there is a limited market, such as paediatric HIV medicines (there are very few paediatric HIV patients in high-income countries) or combination tablets containing medicines from different patent holders (patent holders may prefer to market combinations of their own medicines, even if clinically inferior). Generic manufacturers may be interested in developing such formulations but patents may prevent them from doing so.

• Supply risk. Patented products are normally available only from a single supplier. This may increase the risk of supply shortages, in case demand exceeds production volumes or in markets that are not prioritized by the supplier. For example, in 2015, South Africa experienced difficulties in obtaining sufficient supplies of the HIV medicine lopinavir/ritonavir. Generic versions were available elsewhere, but not in South Africa because this product is patented in South Africa [7,8].

Remedies and their potential impact

A number of remedies to overcome the above challenges do exist within the framework of the patent system. These remedies can be grouped in two main categories:

• Voluntary or collaborative approaches: notably the use of voluntary licenses. An innovative solution created and supported by UNITAID is the Medicines Patent Pool. The Medicines Patent Pool negotiates voluntary licenses for HIV medicines, and functions as a “pool” for such licenses – i.e. a one-stop-shop where licenses for multiple products are available3.

• Approaches based on the use of “TRIPS flexibilities”: notably compulsory licensing, parallel importation, stringent patentability criteria and opposition procedures. UNITAID is supporting two projects (by the Lawyers Collective and the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition) that aim to facilitate access to medicines through the use of TRIPS flexibilities.

UNITAID believes that both voluntary and non-voluntary approaches can play an important role in facilitating access to medicines, and that they complement and can reinforce each other. Through its projects, and in line with its mandate, UNITAID supports both voluntary pooled approaches as well as the use of TRIPS flexibilities in selected countries. As a result, UNITAID has gained some insights in their potential impact, summarized in Table 1.

Notes: - For a summary of methodology and sources, see Annex 1.

- The methodology used to estimate the potential impact of increased access to TB drugs differs from that for estimating the impact of increased access to HIV and hepatitis C medicines. As a result, for HIV and hepatitis C, estimates on the number of patients cured/deaths averted are not available.

While these numbers are estimates/projections, they show the importance – and the potential for significant impact – of both approaches.

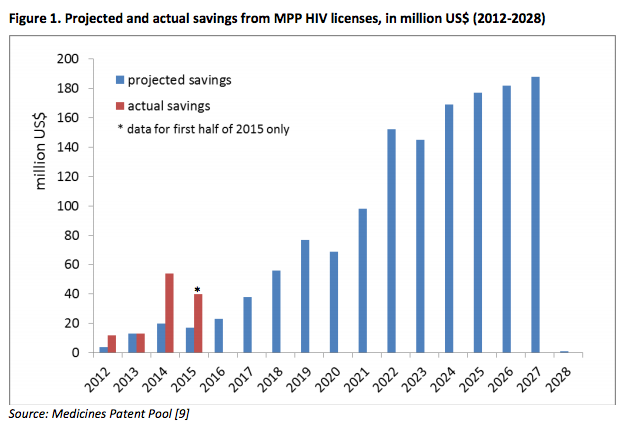

It may be noted that i) the methodology used for the HIV and hepatitis C estimates is similar and ii) actual data are available for pooled voluntary licensing for HIV medicines through the Medicines Patent Pool. These data show that the actual impact (savings) over the period 2012-2014 was double the estimated amount. The actual savings in 2015, too, surpass the amount estimated (see Figure 1).

As these projected and actual savings show, both voluntary measures (notably pooled voluntary licensing) and the use of TRIPS flexibilities can play an important role in improving access to medicines.

In principle, the same approaches can also be used in the context of other diseases; this is explored in a paper commissioned by UNITAID [10].

Practical constraints and “TRIPS-plus”

In practice, the use of TRIPS flexibilities is less extensive than one might expect, due to pressure on countries to refrain from using them. In addition, “TRIPS-plus” provisions in, notably, bilateral and regional trade agreements undermine and limit countries’ ability to provide for and use these flexibilities, or introduce new exclusive rights (such as data exclusivity)5.

“TRIPS-plus” requirements can also undermine access to medicines in low- and middle-income countries, as UNITAID has experienced first-hand when generic HIV medicines funded by UNITAID were detained during transit in Europe on allegations of intellectual property infringement [11]. While these medicines were eventually released, such interceptions can have considerable costs in terms of human health (e.g., risk of interrupted treatment, deteriorating people’s health and increasing the risk of the development of resistance – which in turn would require a switch to more expensive medicines).

Consider “delinkage”

One idea that seeks to address the root cause of the tension between stimulating innovation and ensuring widespread access to innovative medicines is to break the link between funding/rewarding innovation and the price of the resulting product. This would require funding and rewarding innovation directly rather than via patent protection. By enabling early competition for innovative medicines, “delinkage approaches”6 could also result in more affordable prices for new medicines, and thus have the potential to significantly expand access to innovative products. R&D approaches that encompass the principle of “delinkage” therefore merit to be seriously explored.

UNITAID has commissioned a “think piece”, exploring through projections the potential implications of “delinkage approaches”6 for funders, consumers and producers. The paper explores the effect of “delinkage” on prices of, and access to, an innovative product, while keeping the rewards to the innovator constant. UNITAID believes that this paper7 (see also Annex 2) may be relevant to the deliberations of the High Level Panel.

ANNEX 1: Methodology of impact estimates

Impact estimate 1: HIV medicines8

Assessments9, undertaken by the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) for UNITAID, estimate the potential future savings to the international community (donors, national governments and out-of-pocket expenses by patients) due to generic competition for HIV medicines, enabled by the MPP’s voluntary licenses. The assessments estimate the impact of generic competition for 10-14 HIV medicines licensed to the MPP over the timeframe 2015-2028 in 100-127 low- and middle-income countries (the number of countries varies per medicine/license). It is estimated that generic competition enabled by the MPP’s voluntary HIV licenses would result in savings of US$ 1063-1392 million.

According to the estimates, impact will increase over time (as shown in Figure 1) as generic products are being developed, registered in an increasing number of countries, included in national treatment guidelines, and ultimately used by increasing numbers of people.

A proposal submitted to UNITAID in 201410 estimates the potential savings from enabling generic competition for 4-6 HIV medicines11 through the use of TRIPS flexibilities in 4 countries. The proposal estimates the potential savings for each product in each country for one year. Using the data in this proposal as a basis, UNITAID has been able to prepare a multi-year estimate, following the methodology used for the MPP’s HIV estimates; potential savings from the use of TRIPS flexibilities in those 4 countries could amount to approximately US$ 678-942 million over the period 2015-2028.

Impact estimate 2: two TB medicines (bedaquiline and delamanid)

A study12, commissioned by the MPP, has estimated the potential impact of generic availability of two new TB medicines (bedaquiline and delamanid), predominantly in terms of the number of additional people that could be treated if generic versions of these two medicines would be made available. The study, which focuses exclusively on people with multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB)13, estimates the impact of generic availability for the timeframe 2015-2035.

The study assumes that potential licenses would have a geographical coverage similar to some of the MPP’s licenses for HIV medicines. Specifically, it is assumed that a voluntary license would include 116 low- and middle income countries that account for approximately 65% of global MDR-TB cases14. For such a voluntary license, the study finds that 14,000 additional MDR-TB patients could be cured, 31,700 deaths could be averted and cost saving of US$ 184 million could be realized.

It has been estimated that, of the MDR-TB cases found outside these 116 countries, approximately 14% are in high income countries (mostly Russia), while the remaining (+ 21% of all MDR-TB cases) would be found in certain middle-income countries that are not included in the MPP’s HIV licenses14. Assuming that those countries with + 21% of the MDR-TB burden where to use TRIPS flexibilities in order to enable the availability of generics, and that the impact would be proportionate to that in the 116 countries, this would amount to more than 4,500 additional MDR-TB patients cured, more than 6,800 deaths averted, and potential savings of US$ 59 million.

Impact estimate 3: one hepatitis C medicine (daclatasvir)15

An assessment16 by the MPP estimates the potential future savings to the international community (donors, national governments and out-of-pocket expenses by patients) if generic competition would be possible for one hepatitis C medicine (daclatasvir). The study estimates the impact of generic competition for daclatasvir over a 15-year timeframe (2015-2030) for 4 scenarios: inclusion of 90, 108, 114 and 127 low- and middle income countries in the license.

Since the study was undertaken, the MPP has signed a voluntary license for daclatasvir, covering 112 countries. Its expected impact therefore would be between that for the 108 and the 114 country scenarios, i.e. this license would result in estimated savings of US$ 1294 – 1700 million.

As the study methodology estimates impact/cost savings based on lower prices due to the availability of generic medicines, the impact estimates do not depend on whether generics are available in countries due to voluntary licenses or due to other mechanisms, such as the use of compulsory licenses or other TRIPS-flexibilities. Therefore, the difference between the 127-country scenario and the other scenarios (pertaining to countries now included in the MPP license) indicates the potential savings for the use of TRIPS flexibilities in an additional 13-19 countries. These savings would range from US$ 768-1174 million.

It should be noted that:

- Due to the methodology used in the study, the estimates do not cover all low- and middle income countries; notably Brazil and China are not included in any of the scenarios. Inclusion of one or both these countries (with large populations and relatively large numbers of people with hepatitis C) would significantly increase the potential savings.

- The estimates are comparable, as they are based on the same methodology and assumptions. The methodology is similar to that used for HIV medicines (estimate 1).

- Whether the projected impact will be realized in practice depends on there being an actual market for hepatitis C medicines. This is less certain for hepatitis C medicines (compared to medicines for HIV or TB) as there is virtually no donor funding for hepatitis C treatment, and many low- and middle-income countries have no established treatment programmes for hepatitis C (yet). This caveat applies to both voluntary licensing approaches as well as the use of TRIPS flexibilities.

- Relative to the impact of the voluntary license, the potential impact of the use of TRIPS flexibilities in the additional 13-19 countries is underestimated, as these are the countries where originator prices tend to be higher than in most low-and middle income countries17.

ANNEX 2: Projections regarding delinkage effects

UNITAID commissioned a paper to explore, through projections, the potential effects of delinkage. The paper estimates the distribution of benefits between producers and consumers, and estimates deadweight loss and the outcomes regarding the percentage of persons with access to a medicine in different countries (by World Bank income groups).

The projections relate to three scenarios: 1) a single worldwide price, 2) a single price for countries in each of the four World Bank income groups, or 3) a different price for each country. For each of the three scenarios, the delinkage comparisons were designed to be revenue-neutral for producers (i.e. the earnings of producers would remain the same).

As in any analysis based on modelling, the scenarios are based on assumptions that may be more or less realistic. What matters most, therefore, are not the absolute numbers or outcomes but the changes therein, which indicate who would stand to gain and who would stand to lose if delinkage were to be implemented.

For more details, including on the methodology and assumptions, please refer to the paper “An economic perspective on delinking the cost of R&D from the price of medicines”, available at http://www.unitaid.eu/images/marketdynamics/publications/Delinkage_economic%20perspective_Feb2016.pdf

Bibliography and References

REFERENCES

1. Public health, innovation and intellectual property rights. Geneva: WHO, 2006. Available: http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/report/en/

2. HIV medicines: technology and market landscape. Geneva: UNITAID. March 2014. Available: http://www.unitaid.eu/images/marketdynamics/publications/HIV-Meds-Landscape-March2014.pdf

3. Hepatitis C medicines: technology and market landscape. Geneva: UNITAID. February 2015. Available: http://www.unitaid.eu/images/marketdynamics/publications/HCV_Meds_Landscape_Feb2015.pdf

4. Chirac P, Torrelee E. Global framework on essential health R&D. Lancet 2006;367:1560-61.

5. The Global Strategy and Plan of Action on Public Health, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Geneva: WHO, 2011. Available: http://www.who.int/phi/publications/Global_Strategy_Plan_Action.pdf

6. Report of the Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development: Financing and Coordination. Geneva, WHO, 2012. Available: http://www.who.int/phi/CEWG_Report_5_April_2012.pdf

7. Lopez Gonzales L. New agreement could help end ARV stock outs. The South African Health News Service. 18 December 2015. Available: http://www.health-e.org.za/2015/12/18/new-agreement-could-help-end-arv-stock-outs/

8. Kahn T. MSF urges state to break patent on HIV drugs. BusinessDay. 28 October 2015. Available: http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/health/2015/10/28/msf-urges-state-to-break-patent-on-hiv-drugs

9. Progress and achievements of the Medicines Patent Pool 2010-2015. Geneva: Medicines Patent Pool. 2015. Available: http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/wp-content/uploads/MPP_Progress_and_Achievements_Report_EN_2015_WEB.pdf

10. Ensuring that Essential Medicines are also affordable medicines: challenges and options. Discussion paper. Geneva: UNITAID. 2016 (forthcoming).

11. UNITAID Statement on Dutch Confiscation of Medicines Shipment. Geneva: UNITAID. 2009. Available: http://www.unitaid.eu/Resources/News/156-Unitaid-Statement-On-Dutch-Confiscation-Of-Medicines-Shipment

12. The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Implications for Access to Medicines and Public Health, UNITAID. 2014. Available: http://www.unitaid.eu/images/marketdynamics/publications/TPPA-Report_Final.pdf

NOTES

1. See http://www.unitaid.eu/en/resources/publications/technical-reports#cross for more information. See also databases developed by the Lawyers Collective (http://www.lawyerscollective.org/drugs-list) and the Medicines Patent Pool (http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/patent-data/patent-status-of-arvs/).

2. UNITAID’s mandate relates to HIV/HCV co-infection.

3. The Medicines Patent Pool recently started to work on hepatitis C and TB. For more information, see http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/

4. Assuming a cost of US$ 150 per person per year for 1st line HIV treatment.

5. For a review of the potential implications of TRIPS-plus provisions in free-trade agreements, see for example [12].

6. Approaches where the final price of new and innovative medicines is not linked to the cost of innovation, but where innovation is rewarded through different, more direct means.

7. An economic perspective on delinking the cost of R&D from the price of medicines. Discussion paper. Geneva: UNITAID. 2016. Available http://www.unitaid.eu/images/marketdynamics/publications/Delinkage_economic%20perspective_Feb2016.pdf

8. The estimates in this section are partly based on unpublished material. UNITAID would be willing to explore if and how this could be made public, should the Panel members consider this necessary.

9. MPP reports to UNITAID, 2012-2015; [9].

10. ITPC proposal to UNITAID, 2014 and ITPC first project report, 2015.

11. The number of medicines varied among the 4 countries.

12. Trinity Partners and Elizabeth Gardiner. TB Strategic Expansion Assessment. April 2015. Available: http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/wp-content/uploads/MPP-Intervention-in-TB-Trinity-Partners-.pdf

13. These are patients with few other options, thus, these new medicines are particularly important for them.

14. The percentage of MDR-TB cases has been estimated by UNITAID based on: WHO, Use of high burden country lists for TB by WHO in the post-2015 era: summary. Available: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/high_tb_burdencountrylists2016-2020summary.pdf and WHO, MDR-TB burden estimates for 2014. Available: http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/download/en/

15. The estimates in this section are partly based on unpublished material. UNITAID would be willing to explore if and how this could be made public, should the Panel members consider this necessary.

16. MPP proposal to UNITAID, 2015 (Annex 14). The assessment is based on the scenarios and methodology in the report: Dalberg. Assessing the feasibility of expanding MPP’s mandate into hepatitis C. April 2015. Available: http://www.medicinespatentpool.org/wp-content/uploads/MPP-Intervention-in-Hep-C_Dalberg_CDA.pdf; scenarios in this report have been updated and refined.

17. The methodology assumes a low originator price for 90 countries and a higher originator price (of US$2000/treatment) for the other countries. However, in a number of countries, it is likely that the originator price would be (significantly) above US$ 2000. These countries are relatively over-represented in the 13-19 countries that are included in the 127-country scenario but not in the other scenarios.